Homegrown Seeds

I don’t know exactly when it began. Maybe it was that sunny autumn day when I was doing some cleanup in the garden and noticed an occasional glisten reflecting from the tall, dark, spiked flower heads of Purple Coneflower, Echinacea purpurea. Drawing closer to investigate, I broke the flower head open, dislodging droppings of small beige seeds, called nutlets.

Or maybe it was while reading books on heirloom gardening during a time when I was studying horticulture, the ethics in agriculture and how to hybridize petunias. The more I learned the more I felt the need to collect all types of seeds from my local region. I learned then, as concerns were arising over the effects of genetic modification of plants, about seed banks and the quest to preserve the genetic heritage of plants.

My studies taught me that there are three basic categories of seeds: open pollinated/heirloom seeds, hybrid seeds and genetically modified/engineered (GM or GE) seeds.

WHICH SEEDS TO SAVE?

Open pollinated seeds are collected from a group of plants of the same variety, where the individual plants “openly” share their pollen—transferred via bees, other insects or wind—amongst themselves. This cross-pollination happens among wild plants all the time, allowing for species to contain a diverse genetic history and adapt to their bioregions. Open-pollinated garden seeds of varieties that have been distinct for generations are often referred to as heirloom seeds.

If you want to collect garden seeds that are the same as the variety they came from, only one variety should be growing in the area. If there are two different open-pollinated varieties next to each other, the seeds you collect to plant the following year will likely be a cross of the two and have a mixture of traits from both.

When plant breeders purposely allow two or more varieties to pollinate back and forth, collecting the seed to grow out the following year, that is hybridizing seeds. They may be looking for improved traits such as disease resistance, color and productivity. You may notice on seed packets after a name of a variety the term “F1.” That means it is a first generation hybrid, and the seed collected from those plants will not necessarily produce the same traits.

The third type of seed is one that should not, or cannot, be saved—some of these plants don’t even produce seeds and some are restricted by patent. These are the genetically modified organisms or genetically engineered seeds. The genetic material in these seeds has been altered using technology that inserts a gene from one organism—plant or animal—into the plant organism. This type of seed is more targeted to large-scale agricultural methods— for example, soybeans. The soybeans are altered to contain a gene that makes them tolerant of the herbicide glyphosate (trademarked as Roundup). This allows the farmer to plant a field of GMO soybean seeds and then come back a few weeks later to spray the field with glyphosate, killing the weeds but allowing the soybean plants to live and grow.

BANKING ON SEEDS

Seed banks were designed to save seed. They hold a collection of heirloom, non- GMO seeds from a particular region, a period of time or maybe a special collection of an indigenous group of people. The purpose is to save the seed and thus the genetic diversity of the plant.

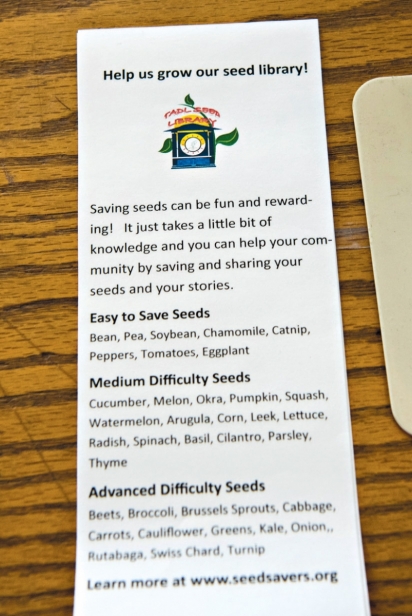

A few years ago I started hearing about seed libraries. The purpose of a seed library is not only to provide seed for planting, but also to accept donations back. At a seed library, you can “check out” seeds and plant them; then if you are able to collect some seeds from them you can keep some for yourself and return some to the library. You may also make donations from other plants that you have grown yourself.

In the spring of 2018, Michele Howard, then a reference librarian, now the library director at the Traverse Area District Library (TADL) opened the district’s new seed library. There is also a seed library at the district’s Fife Lake branch. At TADL, the seeds are housed in an old wooden card catalog that was no longer being used by the library. They are free to anyone who wants them. To get the library started, commercial seed packets were accepted from local businesses and the TC Community Garden. Other donations from gardeners came in along the way. By fall of 2019, all the remaining seeds had been checked out, and the seed library is now closed until spring 2020, when new donations will be available. Howard says this will be in late March or early April, when seeds can be started indoors and peas planted outside (wait until the soil warms to 45° first!).

I inquired about seed libraries with Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, one of the largest heirloom seed companies in the U.S. and a frequent donor to seed libraries. Staff writer Kathy McFarland replied, “I think seed libraries are a great idea. The concept is still too new to know its long-term effects and outcomes. I don’t know how many people who check out seeds actually return seeds after a harvest. Another concern is cross-pollination of seeds that are returned. However, those are minor concerns. Even cross-pollinated vegetables grown locally are better than no vegetables.” Donation of seed packets seems to be the way that seed libraries obtain the majority of their seeds, but there are some efforts being made by local seed savers.

LOCAL SAVERS

Brenin Wertz-Roth and Jamie Schaub of Poesis Farm in Traverse City are both passionate seed savers. They conduct educational programs and seed saving workshops in the community. You could also find Brenin at the Northern Michigan Small Farm Conference tending the Seed Lounge table, a place where farmers can pick up or donate seeds. Brenin shared with me his hopes of developing regional varieties. “It’s not just about saving seeds. The next level of the local food movement is about creating a deeper community of seed savers.”

Brenin says he has been inspired by other food regions that have strong seed saving communities. “The deepest beauty of seed saving is the rich tapestry that weaves itself throughout the community. It makes sense to create a community of seed savers. That’s one of the reasons that the seed library [at TADL] is cool.”

As for the positive impact of seed libraries, Jamie added, “The benefits of a seed library are abundant. The most obvious to me is having local seed genetics that are adapted to our climate. Additionally, it is simply another source of community building. It is the practice of sharing, and of showing generosity as well.”

Grow Benzie is a community center, not a library, but they too have developed a seed library. Executive Director Joshua Stoltz told me, “At a seed saving meeting in 2017, Kim Ison approached me and said, ‘We should have a seed library at Grow Benzie.’ Lots of folks come to Grow Benzie with ideas, but Kim had more than a passion— she was willing to put in the work when no one was watching.” A new person has stepped up to take care of the seed library for 2020—local artist Becky Thatcher, another passionate gardener and seed saver.

You can find an online state map of seed libraries at MISeedLibrary.org. Organized by Ben Cohen of Small House Farm in Sanford, MI Seed Libraries has a vision that “every community in Michigan has a seed library and access to locally adapted seeds and education.” They are encouraging involvement in a new project called “One Seed, One State.” In its inaugural year, Michigan farmers and gardeners are being asked to grow and save seeds from ‘Provider’ beans, described on the website as “a delicious green snap bean with a bush growing habit and great vigor and disease resistance, known for its ability to germinate in cool soil.”

Ben, in addition to running the website, farming, writing books and saving seeds, is coordinating what has become known as the largest seed swap in Michigan, the Central Michigan Seed Swap. This year it is a day’s event with speakers, vendors, kids’ activities and the swap tables. It will be held at The Chippewa Nature Center in Midland on Sunday, February 23, and more information can be found through its Facebook page.

We wouldn’t have the food we have today without all of the human effort throughout history in seed saving—selecting traits for unique and wonderful flavors and colors, carrying their genetics through time and passing along the stories. We grow and collect every year, year after year, sharing with our communities and saving for the future. Because of seeds, going to the farmers’ market is like a food adventure through place and time: vegetables, herbs, flowers and fruits that bring us flavors and beauty from around the world and breads baked from ancient grains that are growing here in our region today. They have become part of our food and farming community. It is nice to think of a future regional variety. Think about it. It all starts with a seed and community.

Growing For Seed

Growing plants for their seed is a bit different than growing for their edible parts, and the two are usually at odds with each other. Think about it—we eat leaves and roots, pods and shoots. Even the seed-bearing fruits we eat are often harvested before their seeds are finished or matured. Growing for seed requires growing a plant through its full life cycle—an interesting endeavor all on its own if you get excited by botany. Some leafy plants, like lettuce, spinach and cilantro, will seed out later in the summer if left alone to bolt and make seed heads. Other plants, like beets and parsley, are biennial and need to be left through the winter to set their seeds in their second year. Beans and peas need to be left on the vine until the seeds bulge and the pods dry out, and cucumbers get left until they are big, yellow, unappealing but ripe fruits. And then there’s the harvest, storage and germination testing to learn about. To get started in seed saving, find resources at MISeedLibrary.org or SeedSavers.org.