The Ubiquitous and Delicious Egg

The first solo cooking experience I can remember was frying two eggs to serve with toast. I was 9 years old, the adults were still asleep, I wanted eggs. This first attempt ended with smoke alarms and screaming—and less-than- impressed parents. Since that morning, I’ve been eating eggs at an average rate of two or three times per week. Quick math puts that at a roughly 10,000 eggs since my eighth year. Which is equal to the lifetime production of about 18 hens.

And why not eat tens of thousands of eggs? Eggs provide essential nutrients the body needs while being affordable, available and delicious. They provide needed protein and fat. They’re pre-packaged with vitamin D, calcium, potassium, riboflavin, vitamin B12, zinc, selenium and choline.

According to the records, humans have eaten eggs of some sort since we discovered nests. The East Indians were the first to harvest eggs around 3200 BCE. The Chinese followed suit almost 2000 years later when they domesticated fowl. Europe began to eat eggs during the Roman Empire. Yet eggs didn’t become ubiquitous for breakfast until the industrial revolution. Before then, breakfast was considered a sin. Thomas Aquinas even considered it gluttonous to eat too early. Protein-rich meals were for later in the day. With new demands on workers, and long days without a meal, a heartier breakfast was sought. As a source of protein and healthy fat, eggs were the perfect match.

But, back to eggs, as they aren’t only for breakfast.

There is more than one kind of egg. Depending on availability, we may enjoy the rich egg of a duck or goose, the dense nutritious punch of a quail egg, or a yolky pheasant egg. In Australia, emu and ostrich eggs are available. The focus here is on the humble chicken egg. It is the torch carrier through history. It rises above for democratic plenty.

Early production remained of the backyard variety until the early 20th century. Before that, egg production never scaled up past 400 birds or so. In the 1930s, indoor henhouses reduced bird loss from predators, weather and parasites. In later decades, improvements in sanitation, health and automation increased a single bird’s production to over 250 eggs per year. This ushered in the beginnings of the commercial hen factories that we know today. In the United States, there are now over 300 million birds producing about 75 billion eggs a year.

Of course, not all eggs are equal. A visit to a nearby grocery store reveals the complexity of labels and marketing of the simple egg. First, the sizes are reflective of the combined weight of the dozen, not the size of the individual eggs. Second, the shell color is reflective of the breed of chicken it came from rather than of some innate quality. But consumers often believe that brown eggs are more natural and “Big Egg” is happy to oblige and charge a little more for them.

As for the labels, first the bad news: Egg labels don’t mean a whole lot. All Natural means nothing. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) considers all eggs in their shell as natural. Farm-Fresh also has no meaning. Hormone-free is misleading as hormones are not allowed for use in poultry. Antibiotic-free is misleading because antibiotic residues do not get into eggs; however the label does accurately indicate that the hens were not fed or treated with antibiotics.

More useful are the labels for Organic, Cage-free and Free-range. These are all regulated to some degree and give consumers an understanding of how the eggs were produced. Cage-free generally means the hens were packed in a large building without individual cages. Free-range minimally means that the large, cage-free building had a small door with a small outdoor space available, should the hens be able to find it. Certified organic means organic feeds, no antibiotics and free-range. (For a useful “scorecard” on the differences between organic egg brands, go to Cornucopia.org.)

None of these certifications means the chickens lived the good life. For that, it’s best to seek out a local source or pasture-raised, or both. There’s neighbors with extras, farm stands, farmers’ markets and local-focused grocery stores. The eggs will be fresher, the chickens healthier as they feed off of plenty of grass (natural omega-3 boost!) and juicy, meaty grubs.

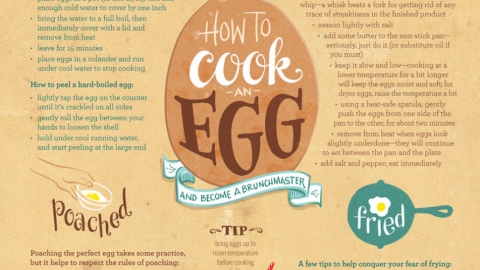

When it comes down to it, eggs of any kind are a healthy addition to any meal. After eating thousands of them, I continue to learn new ways to prepare an egg. It was only recently that I discovered the creamy brillance of scrambled eggs cooked “low and slow,” as the New York Times wrote. Folded over and over for 15–20 minutes, depending on your patience, the result is light, creamy and mouth-melting curds. Or, try flash-frying an egg in a wok to enjoy crispy edges.

There are plenty of recipe books for eggs, but none like Michael Ruhman’s. His book, Egg: A Culinary Exploration of the World’s Most Versatile Ingredient, begins with a flow chart exploring the many uses of eggs. The flow chart is in the book as a four-foot-long pullout. It covers the different decisions to make right from the beginning with the raw egg in its shell. Do you want to use it whole? Or separated? Cook it in the shell? Or out of the shell?

The book and the poster are a celebration. As he writes:

“In the kitchen, the egg is neither ingredient nor finished dish, but rather a singularity with 1,000 ends. Scrambled eggs and angel food cake and ice cream and aioli and popovers and gougeres and macaroons and a gin fizz aren’t separate entities. They’re all part of the egg continuum. They are all one thing. The egg is a lens through which to view the entire craft of cooking. By working our way through the egg, we become powerful cooks.”

There are so many paths to take and so many eggs to eat. I’m glad I started young.