Our Local Foodshed at 10

A milestone, like a memory, makes a mark in time and place from which to measure, or maybe just recall, a journey. Such a milestone anniversary for this publication allows us a look back at ten years and more of northwest Lower Michigan’s foodshed. Not a timeline, nor an encyclopedia, but a few dips into the pool of farmers, merchants, foodcrafters and, indeed, all of us eaters, who together, aware of it or not, have been building the localfood web that we enjoy today.

One evening in mid-March, with snow still blanketing the landscape and winter maintaining a chokehold on Northern Michigan, Petoskey chef and farmer Mike Everts returned home from a cross-country ski to prepare a dinner that was sourced almost entirely from nearby gardens and forests. He filled taco shells purchased from the Grain Train Natural Foods Market with venison, onions, garlic and a homemade habanero carrot hot sauce. He added fresh spinach grown in a local hoop house. That night, only the obligatory avocados broke the “source local” ethos.

For Everts, the meal was a reflection of the strides our local-food movement has made in the past decade, or so.

“I don’t just do it as a farmer and caterer, I eat this stuff every day,” said Everts. “The content of my own diet has gone from 30 percent, to 50 percent, to almost 95 percent local food. The choices in our region have multiplied.”

As owner of Blackbird Gardens and the Real Food Dream Kitchen farm-to-table catering company, Everts may occupy a spot at the top of the food chain. But the local-food movement has trickled down to restaurants, kitchens and farmers’ markets since 2007, when the New Oxford American Dictionary named “locavore” its Word of the Year. Defined as “a person who endeavors to eat only locally produced food,” the word was coined by four San Francisco women who popularized the idea of the 100-mile diet.

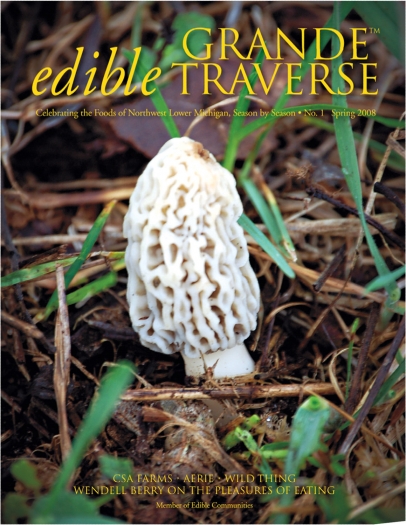

Locally sourced food products in our region are now as common as spotting morel mushrooms after a spring rain. The speed at which the average Michigander has placed value on local and cleaner food sources is impressive, said Timothy Young, CEO of Food for Thought, which produces organic jams, salsas and preserves in Benzie County.

“I track the data and it’s a bit mindblowing what has happened in the last 20 years. When I started my company in 1995, only 3 percent of consumers were willing to spend money on a food product for reasons other than quality and convenience. That’s been changing at a revolutionary pace and now over 40 percent of consumers are willing to pay a premium for food that brings an environmental, health or social value.

“Our food movement, as many industries before it, is fueled by someone brewing in their garage, or baking bread in a church kitchen.”

The subject of local food is just as prevalent in conversations, in our music, our art and our prose, finds Anne-Marie Oomen, an author, poet and playwright who lives near Empire.

“In our own community meals, dinner parties and picnics we are more and more conscious of the 100-mile rule, or in our case, Great Lakes approximates for sourcing our food … and placing attention on ‘local’ and regional food sources. ‘Where’s it from?’ is a common question I ask now.”

AN EDIBLE LITERARY JOURNEY

Edible Grande Traverse launched in Spring 2008, in part to celebrate the Northern Michigan food community coming of age. This ten-year anniversary of the magazine offers an opportunity to reflect on how the food community has evolved, and to consider where we’re heading next.

That inaugural, 44-page edition featured a column by Co-publisher Charlie Wunsch about the rebirth of spring and his return home to Traverse City; a story on a chef at the Grand Traverse Resort sourcing local; a profile on local-food hub Cherry Capital Foods, which launched in 2007 and set to work putting local food in over 100 restaurants and dozens of area schools; a story about the uptick in young farmers active in community-supported agriculture (CSA) harvest subscription programs; and a profile of the Grand Traverse Distillery, a harbinger of growth in the local beer, wine and spirits sector.

The launch issue also included Wendell Berry’s timeless essay “The Pleasures of Eating,” first published in 1989, which describes the importance of understanding the connection between eating and the land in order to extract pleasure from our food. “Eating is an agricultural act,” writes Berry, the Kentucky environmental activist, cultural critic and farmer. “Most eaters, however, are no longer aware that this is true. They think of food as an agricultural product, perhaps, but they do not think of themselves as participants in agriculture.” [See page 37 for our tenth anniversary reprint.]

The necessary connection to the local-food economy grew even more prescient by the fall of 2008. Lehmann Brothers had collapsed on Wall Street, the great recession had begun, and Editor Barb Tholin wrote in a column in EGT’sWinter 2008 edition that local farmers’ markets were growing even as the national economy was in a downward spiral. Across the northern half of Michigan’s mitten a movement was afoot, and it was growing organically. Now more than ever was the time to support each other with our dollars, our intentions and our recipes.

Kingsley native Nikki Rothwell, from MSU Extension’s Northwest Michigan Horticultural Research Center and coowner of Tandem Ciders in Suttons Bay, returned to the Grand Traverse region with her husband, Dan Young, in 2004 from the Pioneer Valley in western Massachusetts—one of the birthplaces of the localfood movement in the United States.

“They had ‘Be a Local Hero’ on food items at all their grocery stores and co-ops,” said Rothwell. “I thought, ‘Why doesn’t our new home in Michigan have this type of program?’”

But that same year, the Michigan Land Use Institute (MLUI, now the Groundwork Center) launched its Taste the Local Difference (TLD) guide with a goal of making the entrepreneurial farms in northwest Michigan more visible to a wide variety of potential buyers, whether they were families who buy directly or wholesale buyers such as schools and grocery stores.

Patty Cantrell, who directed MLUI’s entrepreneurial agriculture program, reported in the inaugural edition of EGT that the TLD guide listed 18 local CSA farms in 2007—nearly double the tally from 2004. Cantrell’s story, “The Good Earth: Growing More than Food with CSA,” introduced farmers Michelle Ferrarese and Marty Heller, adding: “the pair is joining the swell of new farmers, most of them young, and many not from farming backgrounds, who are digging deep into their own desire to make a living close to the earth and at the same time are offering people a new way to relate to their food and each other.”

Since then, in what feels like a growing “back to the land” movement, young farmers have started CSAs all over the region. In Leelanau County, 9 Bean Rows, Loma Farm, Birch Point, Second Spring and Bare Knuckle Farm have joined the already established Meadowlark farm. Up in the Petoskey-Charlevoix region, Bear Creek Organic Farm, Bluestem Farm, Daybreak Dreamfarm, Fiddlehead Farm, Gallant Gardens, Open Sky Organic Farm, Peaceful Valley Farm, Pitchfork Farm, Spirit of Walloon Market Garden and Up North Blueberry Farm have all opened since 2008. ‘ The growth of CSA farms mirrored the growth of hoop house farming and season extension, said Jess Piskor, a Leelanau County native who returned and began farming in Northport in 2009. “We are really at the forefront nationally on how to push our veggies to the limit in a cold climate.”

The interest from restaurants in buying local has in turn incentivized small farms like Piskor’s Bare Knuckle Farm to supply produce for them.

RESTAURANTS SOURCING LOCAL

In Traverse City, Trattoria Stella, founded in 2004 and led by chef Myles Anton, and the Cooks’ House, founded in 2008 by chefs Jennifer Blakeslee and Eric Patterson, have shown that it’s possible to create exquisite food using mainly local ingredients. Many others have since taken a seat at the table.

Today, sourcing local on a restaurant menu is no longer a headline grabber — it’s expected. When chef and food activist Alice Waters visited Traverse City this past September, I wrote in the Summer 2017 edition of EGT that she could walk down Front Street, duck into almost any restaurant, scan its menu for locally sourced, organic ingredients, and measure her impact on contemporary American cuisine. That’s how far the Chez Panisse movement has reached. She could also visit countless school cafeterias in the Grand Traverse region and smile as children learn about, and devour, locally sourced fruits, vegetables and legumes grown right here in Northern Michigan.

FARMERS’ MARKETS, CO-OPS AND GROCERY STORES

Farmers’ markets, too, have drawn increasing crowds across the Grand Traverse Bay area, in towns large and small, in parking lots, next to post offices, next to marinas.

Susan Ager, journalist and frequent contributor to EGT, remembers when the only nearby farmers’ market was in Traverse City—a burdensome 45-minute drive from her home in Northport on a Saturday morning, when lots of chores beckoned. Then the Suttons Bay farmers’ market opened, then Northport.

“Last summer, for the first time in 16 years, I left my own organic garden fallow [due to too many summer obligations],” said Ager. “But I knew I wouldn’t have to go without great local produce.”

Yet in 2008, such markets were all seasonal, and EGT Editor Barb Tholin lamented the inevitable closing of farmers’ markets each autumn. Why not have indoor farmers’ markets all winter long, Tholin asked. “Now that we have entered the dormant season, perhaps it’s time to start dreaming. Is our region ready for a year-round farmers’ market? Or two, or three? Are there crops and products enough to make sense of it? Would farmers come? Would shoppers come? What existing facilities could house a winter season market? Which communities could support a yearround market? Might yours? Let’s start talking! Who knows what could happen!”

As it turned out, that very winter two small markets were opening indoors—one at the Depot in Traverse City and one in downtown Frankfort. And the next year the Mercato at the Grand Traverse Commons began hosting a winter farmers’ market from November until April. The bustling market quickly became a mainstay of Saturday morning activity in Traverse City. Boyne City market also went indoors, and over time other markets followed in Petoskey, Charlevoix and Harbor Springs.

“It’s hard to overstate the importance of both the Boyne City and Petoskey farmers’ markets deciding to invest in becoming year-round markets,” said Brian Bates, coowner of Bear Creek Organic Farm in Petoskey. “This has changed how consumers think about purchasing and consuming local food. It has also changed the market farming landscape, providing opportunities for farms and artisans to generate income in the ‘slow’ season and connect with consumers 52 weeks a year.”

But before the surge in CSA farms and farmers’ markets, it was food co-ops and area grocery stores that nudged the localfood movement forward. The Grain Train in Petoskey (and Boyne City since 2013) and Oryana in Traverse City both opened in the 1970s—like Wendell Berry, prophets in a movement that would later gain momentum.

“I would say that, in my neighborhood, Oryana and Meadowlark Farms [which opened in the late ‘90s] were the key pioneers of our local-food movement and I’m forever grateful for all they’ve done,” said Jody Hayden, owner of Grocer’s Daughter Chocolate in Empire. “Their oftenthankless work has led to the remarkable local-food community we have today.

“And don’t forget to credit local financiers such as Chris Wendell from Northern Initiative and Laura Galbraith from Venture North who often agree to fund local-food businesses who can’t get traditional loans,” she adds.

Hayden credits several area grocery stores near her as being early adopters who supported local food, including Dave Hansen of Hansen Foods in Suttons Bay and Dale Schneider at Honor Family Market. EGT contributor Janice Binkert has witnessed an expansion and upgrade of grocery stores in Traverse City, where she lives, to carry more local products such as produce, meat, fish, artisan and organic products. Demand and competition have forced them to enter the local-food movement.

WINE, BEER, CIDER AND FOOD TRUCKS

Northern Michigan’s local-food movement has also benefited greatly from the region’s booming wine, microbrewery, cider and distillery scenes, said Bill Palladino, executive director of the Grand Traverse Foodshed Alliance. In fact, it’s possible that without alcohol and the tourism economy that it drives, our local-food movement wouldn’t be as successful and celebrated as it is today.

The wine trails on Leelanau and Old Mission peninsulas, the tally of microbreweries, cideries and local hops have all surged in the past ten¬ years. Grand Traverse Distillery kicked off a new chapter in the localspirits movement when it launched in 2007 and was featured in the inaugural edition of Edible Grande Traverse. Since then, Traverse City Whiskey, Northern Latitudes in Lake Leelanau. Ethanology of Elk Rapids, Mammoth Distilling of Central Lake and Iron Fish near Thompsonville (Michigan’s first farm-based distillery) have followed suit.

Traverse City made it easier to pair a local brew or craft cocktail with a locally sourced meal or nosh when it made the crucial decision in 2013 to allow food trucks at The Little Fleet and elsewhere in town. “That was a turning point for the democratization of the point of entry for entrepreneurs and a different type of experience for customers,” said frequent EGT photographer, and former city commissioner, Gary Howe.

Now you can jive to hip music at The Little Fleet, munch on a Korean beef taco from Roaming Harvest while sipping an IPA from Short’s, without having to make a table reservation.

FOOD POLICY PUSHES THE ENVELOPE

As the culture of local food has changed in consumers’ minds and on restaurant menus, and as food hub Cherry Capital Foods has eased the distribution of local food to area restaurants and schools, a coalition of advocates and nonprofits has worked behind the scenes to grow the movement. Brian Bourdages of Tamarack Holdings (the parent company of Cherry Capital Foods) remembers how, in 2007, MLUI’s Patty Cantrell gathered stakeholders to talk about the regional food system in advance of the completion of the Grand Vision process.

With the help of visionary Bob Russell, this group would become the Northwest Michigan Food & Farming Network. The network worked on local-food branding, on farmland protection and on growing “farm to school,” which would become the Groundwork Center’s heralded statefunded 10 Cents a Meal program. The network also adopted a broad goal of achieving 20 percent local food by 2020—later included in the Good Food Charter, a policy initiative of MSU’s Center for Regional Food Systems.

Summits such as the Northern Michigan Small Farm Conference, now spearheaded by the Crosshatch Center for Art and Ecology, have grown alongside the focus on local-food policy, as have the Great Lakes Culinary Institute at Northwestern Michigan College and local-food incubators such as Grow Benzie, which launched in 2008 and now accepts food assistance Bridge Cards and “Double Up Food Bucks” at its farmers’ market—as do many other markets in the region.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR THE MOVEMENT?

Great tacos are all over the region now but Gary Howe hopes for more international diversity in local-food options. “We have only scratched the surface of exploring global food. Let’s embrace more Indian and Southeast Asian without watering it down.”

Meanwhile, buying local remains a challenge in more rural Northern Michigan, said Amanda Kik of Crosshatch.

“In Bellaire we have the Friday morning farmers’ market, but the CSA farms are a half hour drive away. We need to talk about what local shopping looks like outside of Traverse City. I can go to a specialty wine shop to get Shetler milk and drive 30 minutes to Providence Farm to get produce, but I just spent half of my day doing that. We need another Oryana or a Grain Train. We need access for real rural families. In Traverse City local food is easy, but not so in Bellaire and other rural towns.”

What can we do to expand the envelope so all are focused on eating local food, not just those with financial, physical or cultural means?

To announce a new TLD local-food branding initiative in 2013, Bill Palladino wrote a column in the Traverse City Record- Eagle titled “GM, Ford, Chrysler and Food,” which challenged us as Michiganders to be as staunchly proud of our local food as we are of our beer and of our automobile manufacturing roots. Then, as now, his words evoke the growth of interest in the local-food economy, and hint at where it might lead.

“Imagine a day when you look down the aisles at your neighborhood grocery store, and at a glance know which products were grown or made here,” Palladino concluded the column. “I can see the TV ad now. It’s being voiced-over by Eminem. As the camera moves in slowly filling the screen with images of swaying green fields and orchards, you can hear the proud angst in his voice as he says, “This is northwest Michigan, and this is what we do.”