Forthwith Come the Spuds

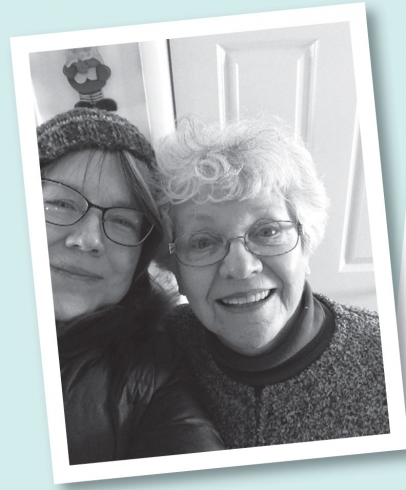

A moment of compassion, please, for my mother: a home economics teacher who hated cooking. She would correct me for the public record: she did not enjoy cooking. Especially under the circumstances.

The circumstances were five children born in the span of eight years and my late father’s veterinary practice housed where most people have a garage. He spent long days on country roads, driving from farm to farm to treat animals. She gave up teaching. Captive to the telephone and the clinic, she took calls and sold mastitis tubes, gave advice and ran the books. It was a chaotic household, with people and animals coming and going at all hours. No telling when that day’s animal emergencies would allow Dad to get home, so there was no regular dinner hour. Instead, my mother perfected the art of keeping a pot of hearty something—goulash, say—warm on the back burner. When Dad pulled into the drive, dusty and tired, she sounded the alert: all hands on deck immediately to put supper on the table.

I learned to cook for crowds, standing at the stove while she called directions from her seat at the dining room table, which was covered in what we called “bookwork.” She recorded receipts by hand into client accounts and created monthly statements to be mailed out, all while teaching me how to brown hamburger. “Get the heavy pot out of the lazy Susan. Yes, that one. Unwrap the meat. Put it in the pot. Turn the burner on medium high.” And so on.

Women of her generation were told they should stay home and greet their men wearing heels and pearls, serving up fine cuisine in a beautifully decorated dining room. That pressure has shadowed her for all her 80 years.

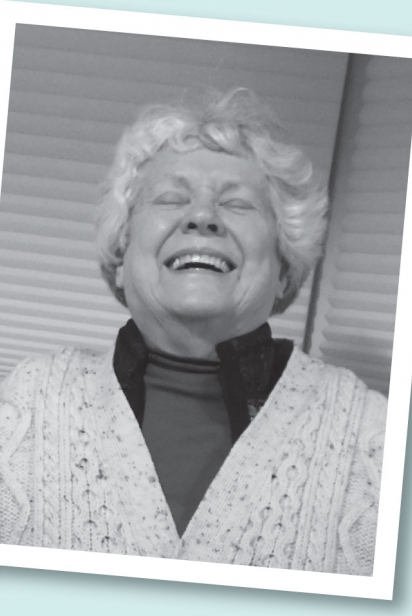

But my mother didn’t have the time to be a fussy cook, and besides, it wasn’t her style. She joked about it, passing around an empty pie plate so we could help ourselves to “Air Pie.”

“Look at it this way,” she’d say. “If I was a good cook, we’d all be fat.”

What she did cook, she served up with a flourish, waving a wooden spoon like a sword over a saucepan of mashed potatoes, declaring, “Forthwith come the Spuds!”

But for all this bravado, imagine the stress she felt over holiday meals, the perfect storm of Good Housekeeping expectations and the arrival of family. Imagine the relief when our tiny village began to host a village Thanksgiving dinner, where all are welcome.

She signed right up. Her job is to make the stuffing, cutting long pans worth of bread and vegetables, which are picked up by some obliging young man and taken to the Methodist church to be cooked. On Thanksgiving Day, we sleep in. Then we drive to the church and eat a good meal on paper plates in the company of our neighbors, farmers and townspeople alike. My mother works the long tables like a politician, greeting old friends and new. She couldn’t be happier.

I called her this October morning. “There’s a mob coming over,” she said, delighted. The Thanksgiving Dinner Committee was meeting at her house. She planned to serve cider and donut holes so she wouldn’t have to mess around with coffee.

How lucky I am for her example: that welcome matters more than perfection. The table may be humbly set, but there should be a seat there for everyone. A moment of thanks, then, for all the people in our lives who, according to their kind—by food or laughter—make sure we all are fed.