Food for All

In regions such as ours all across the United States and Canada, small-scale farmers are exploring agricultural methods that are effective both in producing food and in rebuilding the ecosystems that make food production possible. Big Ag proponents often dismiss these efforts as quaint and inconsequential. But in developing countries around the globe, those same efforts and methods are being hailed as progressive and fundamental to the future health and wealth of those countries.

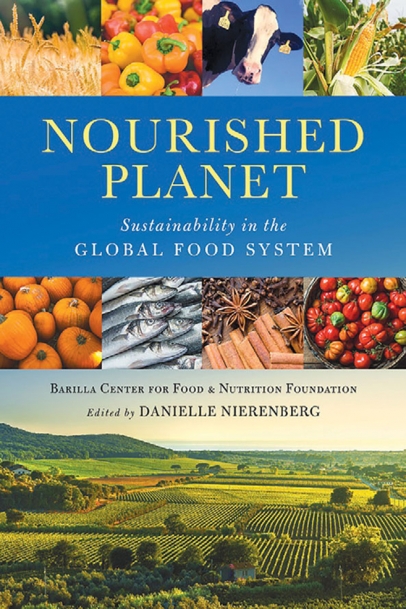

The following is an excerpt of Nourished Planet: Sustainability in the Global Food System. In this new book from the non-profit Food Tank, editor Danielle Nierenberg identifies the ingredients that, when combined, can help us to decrease hunger, prevent micronutrient deficiencies, protect water supplies, preserve seeds, prevent food loss and waste, and protect biodiversity. And the book highlights the need to invest more in farmers, women and youth so that they can make the necessary discoveries and innovations. —EGT

In Chipata, Zambia, a revolution is taking place. The organization Zasaka is getting farmers in that southern African country access to corn grinders, nut shellers, solar lights, and water pumps. Although these technologies might not seem revolutionary, they are producing game-changing results, helping Zambian farmers increase their incomes, prevent food loss and waste, and reduce their load of backbreaking manual labor. But Zasaka is doing more than helping farmers become more prosperous; it is showing the country’s young people how farming can be an opportunity, something they want to do, not something they feel forced to do simply because they have no other options.

This project in Zambia is but one ingredient in a recipe for something truly revolutionary: a radically different worldwide food and agriculture system, one built on practical, innovative, and, most importantly, sustainable solutions to the problems plaguing our current agri-food system.

Farmers, eaters, businesses, funders, policymakers, and scientists are continually learning better ways to increase food’s nutritional value and nutrient density, protect natural resources, improve social equality, and create better markets—in short, to develop a recipe for sustainable agriculture for both today and tomorrow.

This recipe is being developed in fields and kitchens, in boardrooms and laboratories, by farmers, researchers, government leaders, nongovernment organizations (NGOs), journalists, and other stakeholders in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Experts from a variety of socioeconomic and cultural backgrounds are finding ways, firsthand, to overcome hunger and poverty and other problems— while also protecting the environment—in their countries.

Ironically, their recommendations are not that different from those that could be reasonably offered to farmers in North America. Despite all the differences between the developed and developing worlds, there is a growing realization that the Global North’s way of feeding people— relying heavily on the mechanized, chemical-intensive, mass production of food—isn’t working, and that policymakers and donors might be wise to start following the lead of farmers in the Global South rather than insisting that they follow ours.

In Ethiopia, for example, farmers who are part of a network created by Prolinnova, an international NGO that promotes local innovation in ecologically oriented agriculture and natural resource management, are using low-cost rainwater harvesting and erosion control projects to battle drought and poverty, increasing both crop yields and incomes. In India, women entrepreneurs working with the Self-Employed Women’s Association are providing low-cost, high-quality food to the urban poor. In Gambia, fisher folk are finding ways to simultaneously protect marine resources and maintain fish harvests. And hardworking, innovative farmers from all over the world are encouraging more investment in small- and medium-holder agriculture and telling policymakers that farmers deserve to be recognized for the ecosystem services they provide, which benefit us all.

There are countless others whose work is showing the world what a sustainable, global food system, or recipe, could look like. They know that the way the food system works today isn’t the way it has to work in the future.

They understand that we can help build a food system that combats poverty, obesity, food waste, and hunger, not by treating a healthy environment as an obstacle to sustainable growth but by understanding that it’s a precondition for that growth. A food system where science is our servant—not our master—and where it’s understood that costly, complicated technology often isn’t the most appropriate technology. A food system that honors our values—where women, workers, and eaters all have a seat at the table and none are left on the outside looking in.

The world has a real opportunity and an obligation to build that kind of system, and we don’t have a minute to waste. We need to gather the ingredients today so that future generations can build on the recipe for a food system that provides healthful food for all, promotes a healthy planet, and preserves and appreciates food culture.

INGREDIENTS FOR SUSTAINABILITY

There are a variety of ingredients to consider if we are to come up with a successful recipe for sustainable agriculture. First, though, we must understand what we mean by “sustainable,” which is a term that can encompass so much but is often overused and misused. For us, sustainable agricultural systems are able to efficiently and comprehensively meet the food, fuel, and fiber needs of today without compromising the ability of future generations to meet the needs of tomorrow. Our challenge is to create a food system that is not only environmentally sustainable but also economically, socially and culturally sustainable and that helps ensure that we are nourishing people as well as the planet.

Exploring sustainability means exploring the foundation on which food production is built. Air, water, and soil are all important components, and soil—literally the foundation of a healthy food system— is the one most often overlooked. Besides being the physical land beneath our feet, soil stores and filters water, provides resilience to drought, and sequesters carbon. One of the biggest threats to the food supply is the loss of topsoil. Indeed, in the past 150 years, roughly half of Earth’s topsoil has been lost.

Nearly 40 percent of all land on Earth is used for activities related to agriculture and livestock, and all told, some 4.4 billion hectares (roughly 10.8 billion acres, or about 146 times the area of Italy) is suitable for farming. Yet in the past 40 years, 30 percent of the planet’s arable land has become unproductive. In many regions, problems related to soil quality affect more than half of the acreage being cultivated, as seen in sub-Saharan Africa, South America, Southeast Asia, and northern Europe. Each year, the planet loses an agricultural area as big as the Philippines (put another way, we are losing a Berlin-size plot of land every day).

Farmers can revitalize and protect soils by planting cover crops such as winter wheat, rye, and clover. Besides preventing erosion, cover crops, when plowed under, can increase soil permeability and provide a significant source of soil nutrients for future crops. In addition, growing diverse crops rather than relying on a single crop, such as corn or soybeans, can restore soil nutrients and help farmers, both large and small, build healthier, more productive soils.

For example, small farmers in the Global South who are raising cattle can use manure to fertilize crops and promote earthworm production. This not only restores nutrients to the soil and protects its microbiota—the microscopic animals that live in soil by the millions—it also helps farmers save money by eliminating the need to buy fertilizer by the bag and helps mitigate climate change.

“Foodprints,” or the ecological footprints or impacts made on the environment—on air, water, and soil—throughout a food’s production and distribution processes, are tools crucial to understanding and building sustainability. Dr. John Barrett, of the Stockholm Environmental Institute in New York, attributes the growing awareness of ecological footprints to “the increasing acknowledgment of the environmental impact being placed on other countries by the developed world through their consumption patterns. The ecological footprint provides an overview of the developed countries’ dependency on energy and materials.”

It’s no exaggeration to say that today’s food system is like the Titanic: immense, complex, a marvel of engineering, thought to be invincible but racing to its destruction. The difference, though, is that unlike the captain, the crew, and the passengers on the Titanic, we know that disaster awaits us if we don’t change course—and do it fast. The amazing thing about growing food is that when it is done sustainably, it can help mitigate climate change even as it strengthens food security in developing and industrial countries alike.

In 2013, Danielle Nierenberg co-founded Food Tank, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization focused on building a global community for safe, healthy, nourished eaters. Food Tank is a global convener, research organization and non-biased creator of original research impacting the food system. The Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition Foundation (BCFN Foundation) is a private nonprofit think tank, analyzing the effects of economic, scientific, social and environmental factors on food. The foundation produces valuable scientific content that can help people make conscious choices every day about food and nutrition, health and sustainability.