Smelt Days

Memories of the Leland Runs

We often mark time by the seasonal “drop-everything-you’re-doing” things that come around, often centered on the gathering of food. Mid-November in Northern Michigan is deer hunting, January ushers in the ice fishing season, spring is all about morel mushrooms, leeks, maple syrup and smelt.

Or it used to be about smelt. Sometime around the mid-’90s, the smelt population went belly-up and they stopped swarming up into the creeks and rivers, seeking out the 42° water that triggers their urge to spawn. Local outdoor sage Bob Maleski swore they were now “spawning on the beaches” rather than the streams. I’m not sure how he knew that, but Bob had a way of being right about most things like this.

We ate them with great vigor, especially when, as kids, neighbor Jim Van Ness would take my friend Glen Petersen and me to the Cedar Rod and Gun Club Annual Smelt Fry at the Cedar Town Hall every spring. It was a joyous competition, “41 … 42 … 43 … that’s it for me.” They are scarcely more than minnows, but try and eat 43 of anything and you know what I mean.

Platters full of them were a staple on the bar at the Bluebird every April, as someone would always score a pail full or two to donate to the local bar crowd, and Grandmother Leone would fry them up until everyone was groaning. “Don’t bring them in unless they are cleaned, I’ve got a business to run,” she would say. Cleaning sessions alone would gobble up 4–5 hours, easy, and that was after being on the dock until 3 AM.

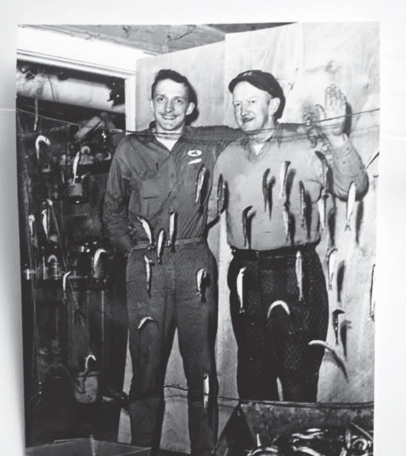

Most of the world catches smelt by walking up a stream, in waders, with a hand net, flashlight or Coleman lantern. And beer. In Leland, we use a much more civilized, “Country Club” style of smelting. Since we fish a deep, fast-moving river, we use a large square “throw net,” basically a section of rebar bent into a square and fitted with a piece of fine-mesh netting. Line is attached at the four corners, brought together, and a main line is tied on where they intersect. Be sure and leave plenty of “bag” in your net to allow it to surround the surprised fish when you pull, but not so much as to make it impossible to resist the strong current of the Leland River.

Believe me, standing on a dock, the bright cone of a 200-watt floodlight coating the bottom, an endless supply of beer, and a rope in your hand, is a hell of a lot better than wading around in some freezing cold, dark stream, in leaking waders, blindly waving around a hand net, only to yield a handful of pretty rocks.

We always fished the north side of the river, near Carlson’s, or later, up by the Stallman shanty, with Lloyd Gibson and his “smelt scope,” an odd contraption that would smooth out the surface of the water to aid visibility. In the heyday, smelters would line the docks, 50 to 100 people all vying for position at one of the hot spots, and you actually had to have someone save your space if you had to go take a leak, or get more beer.

I can still hear Jim Harrison growl at me from on down the dock, “Skip, save me some really big ones. I stuff ‘em.” I would sort a bagful of 10- to 12-inch giants for Jim. I share his preference for the large ones, while most people love the tiny, crunchy, minnow-sized fish.

Across the river were the southsiders— Emil Priest, Roy Buckler, Ross Lang and his dad, Fred, etc.—fishing from out the back of the Seabird, and the friendly competition was on! For several years, Bill Carlson would pull out all the stops and have a true smelt fry, a gigantic party, complete with underwater cameras keeping an eye on the action in the river, and more fresh crispy fried smelt than you could possibly imagine. And beer, lots of beer.

One spring, Bob Maleski and I were trespassing on the Cove’s deck, up near the dam which, on this night, seemed to be the only hot spot in the river. Chef Greg Nicolau was inside, working late preparing the restaurant for spring opening, and he stepped out onto the deck, we assumed to kick us off. He surprised us by making an offer we couldn’t refuse: “Gimme some smelt and I’ll cook them up for you boys.” A half hour later, we were fishing away, while eating a most delectable platter of pan-sautéed smelt between “pulls.” It really didn’t get much better than that.

Smelt only come out at night, after dark, sometimes not ‘til midnight or later. Or at least that’s what we were taught. Every “smeltman” has his daytime story, though. I was enjoying lunch at the Earlybird some years back, and Charlie Hirshfield came in rather excited, saying that there was a dark cloud of smelt up near the dam. Skeptical, I nonetheless grabbed my net and went on down to the south side. The bright blue sunny day allowed us to see quite well through the cold, clear water, and from the deck of the Janice Sue, sure enough, there was a big cloud of something down there. I threw in the net and Charlie tossed a few well-placed rocks in the water to “herd” the cloud over my net, and I pulled in a huge “mess” of smelt. Repeat three times and Chas and I had a five gallon pail full in no time. We still chuckle about that fine April afternoon.

Another time, likely 30-plus years ago, Pete Carlson—Uncle Pete to me—was pretty pleased to have been standing on the dock in front of his eponymous fishery one afternoon when he spotted a dark mass moving upstream. Story goes that he had trouble getting the net out of the water, smelt spilling out in all directions, punctuated by his infectious laugh. If a grizzled veteran fisherman like Uncle Pete was excited about this, you can imagine how this sport can affect a young fisherman.

One particular scenario played out almost every year, always to the delight of us veteran Leland smelters. Smelt scuttlebutt always traveled far and fast, and when fellows from other areas heard that the smelt run in Leland was “on” they would load up their hand nets and waders, and head to Leland. Buoyant excitement quickly turned to confusion when they saw our unconventional methods, but our quickly filling pails moved them to try some rather novel ideas that would lead to other ideas, and provide us with a fine evening’s entertainment.

First, the Coleman lanterns were great for warming you up, and finding the beer, but did nothing to light up the river bottom, so we offered to let them work the perimeter of our aura. The hand nets were completely useless. The water is deep and fast, and so are the smelt. A net with a four-foot handle barely gets the net into the water, so “somebody go find a piece of wood and some rope, or tape, and we’ll extend this net and start scooping smelt.” The resulting gangly 16-foot-long pole net is no match for this current, and either snaps or folds up (cue laughter from the peanut gallery, but we’re just getting started here).

So genius number two gets the idea that if they tie a rope to the net, way out on the end, he can pull it through a cloud of smelt and fill their pails! Now, in theory this seems to make some sense, but in practice it only manages to scare away all the smelt from the vicinity, and no words from us are necessary, so they pack it up for the night.

Fast forward to the next night, and while at the hotel, the beer-fueled brain trust had been hard at it and they have a new plan. While at the local bait shop, they found one of those “umbrella style” minnow nets, “yes, that’s the ticket!” They arrive, renewed, ready to show us how it’s done! To their dismay, the strong current would carry the light, under-built minnow net right on out the harbor mouth if it weren’t tied to the dock post. Now, one of two things comes next: Either they tie a big rock to the bottom of the “bag” in the net, or they tie rocks to the four corners of this “upside-down umbrella.” They can practically taste the fresh smelt sizzling in the pan now. They heave this contraption out into the current and it dutifully sinks to bottom, in full view, ready to ambush the next smelt swarm.

By now, we are loving every minute of this, but are also really getting to know these guys from Owosso, or wherever, sharing our beer and stories, until the moment of truth arrives, smelt! The big guy holding the rope waits … waits … waits, and finally “pulls the trigger.” The whole thing folds up and comes shooting to the surface, smeltless, everyone breathless with laughter. The locals pull together and fill up our new friends’ pails, as by now we have more smelt than we know what to do with, and these boys head home with a story to tell and enough smelt to clean that they’ll see the sun rise before they’re finished.

All those years of “Smelt Karma” must have built up, and came to a head, maybe spring of 1998 or so. As I said, the smelt run had ceased to occur for several years running, but being a “townie,” come mid-April it was easy for me to check each night for a week or so, just in case. Well, one night as I stood staring into the water, in solitude, hey! I see fish, lots of them! I instinctively called Emil Priest, who had “caught” me checking for smelt in the few years previous (leading to great, long conversations about what used to be, but that’s another story). I had raced to my garage and grabbed my lonely smelt net, still hanging on the same nail it had for a decade, and we dropped it down and waited. It didn’t take long to get a nice “pull,” the net turning silver at first yank. We laughed with joy, thinking we had hit the mother lode. The real fun came when I realized we had just caught the nicest batch of alewives ever! I thought Emil and I were going to fall in the river laughing ourselves silly.

The good news: As I said I have been checking every spring, hoping for a return to the good old days of freshly caught smelt. Well, a few years ago, I was greeted by a promising little school of fish, and after a quick dash to Dick’s to get my license, a call to son Derek and gathering up my waiting “smelt stuff,” this father and son scored half of a five-gallon pail full of beautiful Lake Michigan smelt, and what a blast it was, not an alewife to be found. I believe it’d been close to 20 years between catches, so this was kind of historic.

A couple phone calls to the right people, and the next night a dozen or so local boys showed up to relive their childhood dreams and fill up a pail or two. We can only hope that this is a peek into the future of smelting, hopeful that this resource is healing to the point that my children and grandchildren can grow up smelting, and maybe teasing and eventually bonding with a bunch of dudes from Owosso, or wherever.

Smelt in the Great Lakes

The rainbow smelt (Osmerus mordax) is not native to the Great Lakes. The smelt is a saltwater species, though a freshwater population exists in Green Lake, Maine. Fish from this population were stocked into Crystal Lake, Michigan, in 1912. Some of the fish escaped from Crystal Lake and smelt were first caught in Lake Michigan in 1926.

Once established, the smelt population expanded rapidly in Lake Michigan becoming very abundant in the 1930s. The smelt was nearly eliminated from the lake in 1941 to 1942 by an unknown pathogen. However, by the mid 1950s and into the 1960s the fish were once again highly abundant.

Smelt spend most of the year in deep water offshore. There, they feed on benthic invertebrates such as opossum shrimp and amphipods, but smelt also consume other small fish. In the spring, smelt move from deeper water offshore into shallow nearshore waters to spawn. The spawning season lasts for about two weeks in a given area, but the spawning season extends from March into May. The fish begin to move to the mouths of tributaries when the water reaches about 40° F. The fish may swim some distance upstream to spawn or may spawn in shallow water over gravel deltas at stream mouths. Spawning generally occurs at night.

The US Geological Survey annually monitors the abundance of smelt and other Great Lakes fish. These estimates are used to monitor the fish populations in the lake for management and to establish harvest quotas.

Excerpted from the website of the Sea Grant Institute of the University of Wisconsin.

For more information, go to Seagrant.wisc.edu.

Skip Telgard is a Leland resident and third-generation restaurateur of the Bluebird Restaurant, which his grandparents started in 1927.